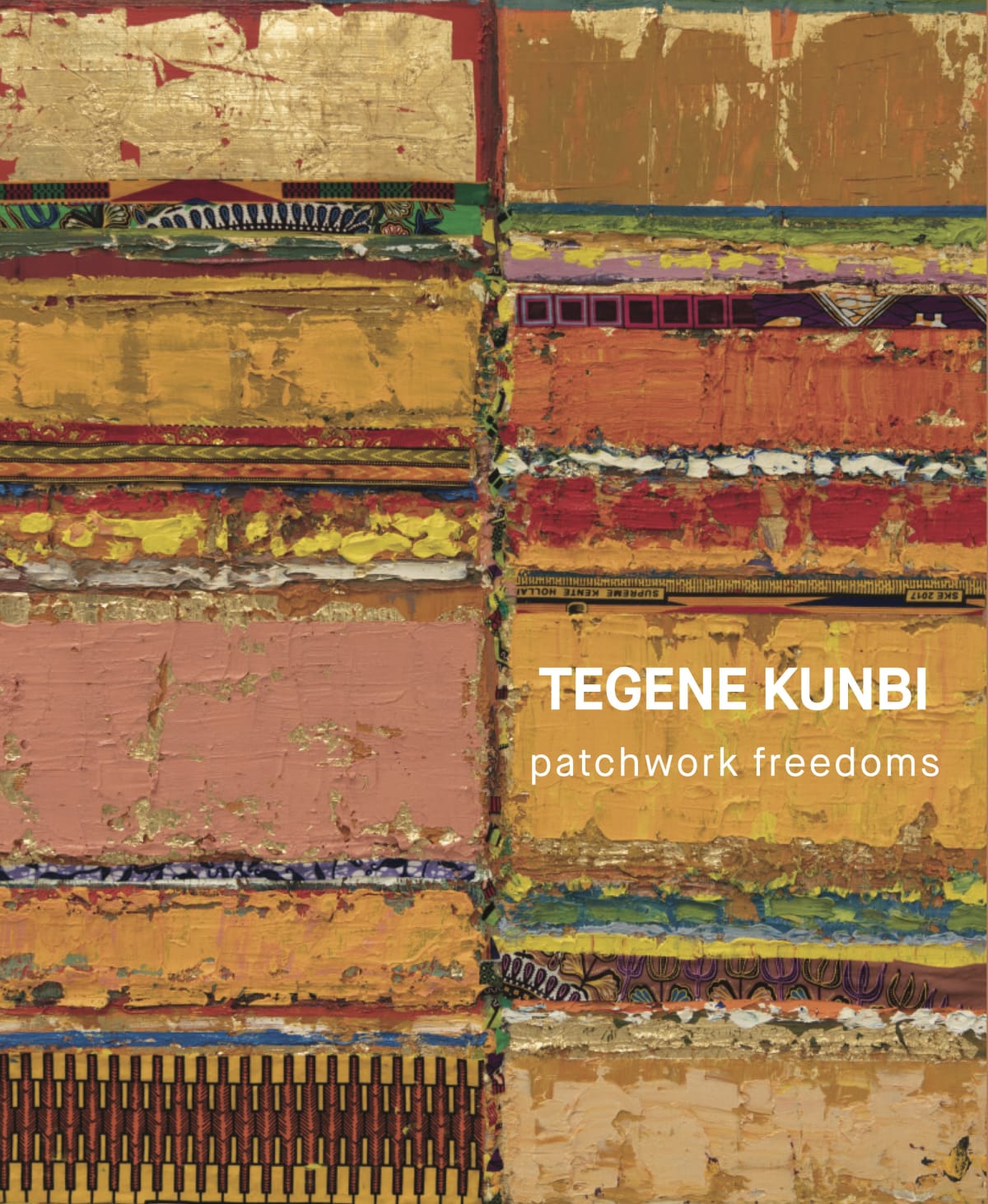

Patchwork Freedoms: Tegene Kunbi

-

Tegene Kunbi

Confusion 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

40 × 30 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Medley 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

40 × 30 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Multiplicity 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

40 × 30 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Cushion 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

40 × 30 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Quit 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

30 x 25 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Cut 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

40 × 40 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Jumble 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

80 × 60 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Something New 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

100 × 80 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Informal Law 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

70 × 50 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Popular Will 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

80 × 60 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Really Broken 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

100 × 80 cm

-

Tegene Kunbi

Absurd Degree 2023

Oil on canvas with textile

100 × 80 cm